On Sunday it’s a bright beautiful Spring day. I decide to leave the refuge of home for a skate in the park foolishly imagining it will be some glorious solitary pursuit punctuated only by the briefest glimpses of fellow human beings distant on the horizon. Unsurprisingly given much of everything else is shut there are very many people out walking, nothing seems very different despite the public health advice to stay two metres apart from each other. I find a patch of smooth tarmac around the back of some sheds that’s hemmed in by fences but decide on balance that it’s a wholly miserable place to be and skate back home. A running joke around Twitter is that all trips outside have become a version of frogger where you only find out two weeks later if you lost. Only the people around me seemingly haven’t decided to play yet. The news is full of stories describing beauty spots filled with people huggermugger.

My trip out in the sun leaves me in the genuinely curious and uncomfortable position of wanting my government to take away my liberty. As someone marginally left of centre but with an overriding libertarian streak I’ve always been torn between two views of the general public. One is a naively inborn, maybe Chompskyan, take that people if well educated on a subject can be trusted to make sound judgements. The other informed more by age and experience is the Hobbesian view that it requires a state to rule in order to prevent our lives being “nasty, brutish and short”. Looking up the full quote I’m taken by the irony of “and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” as I wait to be asked by the governemnt to become solitary and poorer in order to be kinder and save lives. The world is upside down.

By Monday evening the government mandate a lockdown similar to our European neighbours. Similar but vaguer, there’s total confusion on what counts as essential work and it’s still left up to employers to decide whether they should allow people to work from home or close entirely. It appears public health decisions in the UK are devolved and left to individual consciences and economics. The next day a friend of mine gets stopped by the police getting his tools back from the building site that up until the day before he laboured at. They warn him not to be caught out driving so far again. Completely antithetical a fortnight ago. We are allowed to shop for food, medical trips, “essential work” and an hour of exercise. I wonder if skateboarding is still not a crime.

Skateboarding in many ways seems ideal as I had spent much of my youth socially distancing in solitary car parks. I am embarrassingly poor at it but find it most therapeutic. It’s hard to be concerned with anything else when trying to jump and land over a rotating piece of wood on wheels. The car park closest to me is now mostly empty and I start to spend half an hour a day there. One of my friends tells me to be careful as an accident now would place greater strain on the NHS. Now the dust on the initial shock of the crisis is settling the new modus operandi is one of judgement, not only towards our government but towards each other and ourselves. Simple decisions, like whether or not to just leave the house, previously passing wholly without notice now contain an impact on widest society. Italy is frequently invoked as an example and things take on a life and death scale that feels disproportionate, but isn’t. How we isolate, with whom we isolate, how and where we shop, whether we choose to wear face masks, it all matters to each other now. We are simultaneously apart from and noticing each other in new ways.

My parents form my primary concern given their age. The radio implores us to have the difficult conversation about being put on a respirator but they’re not that old and despite Dad’s constant cough I decide some things are best left unsaid. I feel much remorse at not making the effort to see them the last time they were at least on the island of Ireland. The pressing work deadlines that mattered then seem silly now, maybe they were then too. Everywhere people my age are having difficult conversations, trying to ascertain the seriousness with which their relatives are taking it. Is that decision to go out soundly judged? That the hairdresser came last week because in her words “she wasn’t told not to”, now already seems unwise and we all adjust to the idea of exiting this more hirsute than we entered. My father decides that if all holidays are cancelled then getting a cat is essential work. Estimations of risk are judged both by the people taking them and those around them. At the beginning of the week getting in a car to exercise elsewhere is acceptable, by the end it is less clear. As younger people start to be struck down the tables are turned and my Mother starts to check on me and my actions.

I sit at my desk in the bay window, idly tinkering at a laptop and watch a woman delivering a bag of groceries to a neighbour, she wears blue surgical gloves and is crying. Wiping the tear from her eye the gloves are now fruitless. Later the post comes, should I disinfect it? The delivery drivers now stand at the end of the short path to my door waiting for me to acknowledge an arrival. A friendly nod has replaced a signature and at least you know you’re going to be in to receive it. I’ve bought resistance bands for exercising at home and a foot rest for the desk I’m now likely to be sat at for hours a day and weeks if not months to come. The ethics of such purchases, supply chains, use of delivery slots and drivers on zero hours contracts are subtly discussed both in the media and in private conversation, and judged.

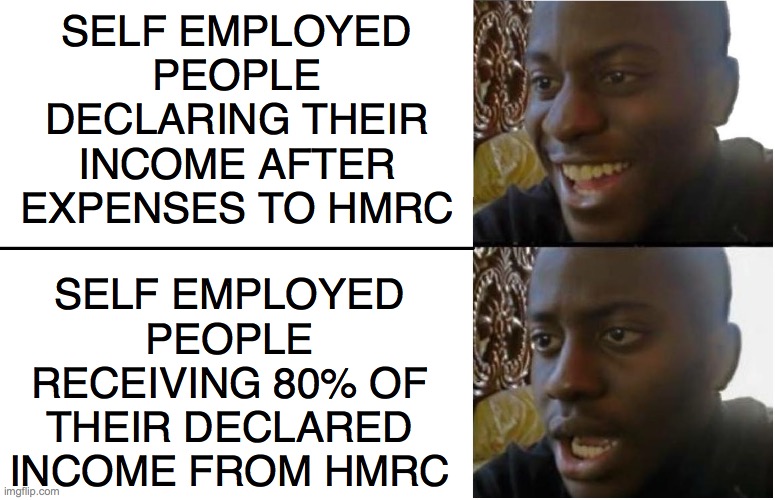

On Thursday we all go outside and clap the NHS and then post about it on Facebook. It’s hard to write cynically about such a mass outpouring of gratitude so I shan’t. The contrarian part of me that struggles with displays of banal nationalism, poppy culture, virtue signalling and just generally taking part in anything is beaten back and I stand loudly applauding on my front step. From nearby streets I hear whooping and am glad for the briefest sight of smiling neighbours. I think about all the poor sods without proper equipment and testing, some of whom even in the best case scenario are likely to end up as patients on their own wards and worse. Afterwards the display is quickly politicised online, many of us clapping will have voted for parties that oversaw their defunding and ignored the prior calls for equipment in case of pandemic. But my mouth has already been stuffed with gold as on the very same day the treasury finally welcomed me into their warm embrace and guaranteed my self-employed income, not that I was short yet. Again there is judgement.

I restrict my consumption of the radio to the Today programme, World at One and PM and take refuge again in music, exercise and cooking. Knowledge of a rising death toll is no use if my sole duty is to stay at home, listen to Satie and protect lives. Much wide eyed eye-rolling comes as the more free spirited of my friends in England suffer full blown agency crises and take solace in bizarre theories. I’ve never really felt like the state was out to get me, more that it just doesn’t particularly care and unchecked would quite willingly sacrifice me to satisfy the economic interests it exists to serve. But if my immediate needs were less well met or I were of a more paranoid disposition or fertile mind I can see how being forced to stay at home would be hard to rationalise. The news that police now have draconian powers to disperse groups of three or more people and are using drones to shame people into leaving beauty spots is hard to bare even when you invoke Italy. Even the less florid amongst us wonder how this will eventually be wound down given the ratchet action with which the state seems to keenly shave liberty away. There is talk of phone records being used to track transmission, techniques perfected elsewhere and if it saves lives here seem hard to argue against. It’s as if every decision can now be plotted along axes of individual liberty, capacity to save lives and economic cost to then become a trolley problem. Living has become an exercise in moral philosophy and utilitarian calculus. The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few and having dithered too long, or worse, the UK government and its people now face their own Kobayashi Maru no-win scenario.

Friday I shop. Having watched Ben Kavanagh’s video from Wuhan, I think that if I can avoid returning to Tescos for at least a week this can only be a good thing. I take from his example and shop with a case. My oversized flight case and two grocery bags transport £140 worth of food home. This is the most I’ve ever spent in a Tesco and I now rue my earlier decision not to have a club card based on privacy. On the one hand we’re told not to panic buy, on the other we’re told to shop as infrequently as possible and that at any time we many need to self isolate for anything up to fourteen days. But this monster shop is as much about mental health as avoiding transmission. If my own Tescos the week before was panicked but grimly normal, that is as-grim-as-normal, Tescos now is an altogether more harrowing affair. You disinfect your trolley handle while waiting to be allowed entry in a queue standing two metres apart, like a plague den nightclub – one in one out. Mask culture is firmly here now, no longer for other places. You look at an aisle before pushing on down it, sizing it up for people, too busy, too irresponsible, too ill looking, you push on. Catch that aisle on the way back round. At the checkout I too am judged, too many of my favourite yoghurts – you’ll have to put some of those back. Not even at the height of the panic did my beloved yoghurts sell out and I have long suspected I’ve been single handedly keeping my local Tescos selling them. But it’s churlish to argue and I swap them. People still smile at each other though and as I cut an odd sight wheeling my case home I give and receive the nod.

This week friends have become ill, thankfully mildly, and in the afternoon comes the news that our leader himself is struck down. Easily politicised his actions are now inspected, did he stand far enough apart? Were any of our politicians taking social distancing seriously themselves as they forced it on us? The punchline if any of it were funny is the sight of his chief adviser, whose hand in the crisis’s handling will be endlessly interrogated, hurriedly scurrying from No 10’s side entrance. Rat like.

In an effort to maintain some semblance of normality I keep on my personal trainer and therapist who’ve both rapidly adapted along with everyone else to video calls. I now get short videos detailing proper form over WhatsApp and sit through an hour and a half on Zoom with my counsellor. Considering my own hierarchy of needs I find them to be remarkably well met, freedom to me has always meant the freedom to create. If anything I feel liberated by the slower pace my life has been forced to take on. At first I’m annoyed when my recycling isn’t collected and then I guiltily confess that I enjoy not having to bother washing and separating it anymore. Friends get in touch asking if I’m alright on my own, each time I respond the same way that “you’re never alone with a cat”. I’m content in my own company.

“Hell is other people” feels apt not only in the widely misquoted sense but in its true original true meaning. Now hell is other people because we are trapped within them, subject to their judgement and judging ourselves as we perceive them to see us.

By the following Sunday as I write we are a week behind in our crisis when Italy’s health service began to crash in theirs, the news stories soften us for a further tightening of the lockdown and more cheerily that at best as a country we can survive with fewer than 20,000 excess deaths if we comply. London seems lost and they are building field hospitals across the country. The second hotspot is less than twenty miles from my parents but I don’t dwell. There is an awful feeling of waiting, as if a great wave of unknown force is coming from behind to crash over us and wonder at who will be left and what the new world will look like after.

By Katsushika Hokusai – Metropolitan Museum of Art, online database: entry 45434, Public Domain, Link